Signs warning of contaminated water and fish, Houston Ship Channel. Photo credit: Lauren Murphy, Amnesty International

In January 2024, both Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch released reports about human rights abuses perpetrated by the petrochemical industry in the Gulf Coast. The AI report is titled The Cost of Doing Business? and addresses the impacts on urban communities around the Houston Ship Channel. The HRW report “We’re Dying Here” looks at rural communities in Louisiana’s Cancer Alley.

The USA is the world’s largest oil and gas producer and accounts for more than a third of global oil and gas expansions planned through 2050. Much of these fossil feedstocks will go to the rapidly growing plastics and petrochemical industries in the region between Houston and New Orleans, the “sacrifice zone” that already contains the highest concentration of petrochem plants in the country.

Texas – Houston Ship Channel

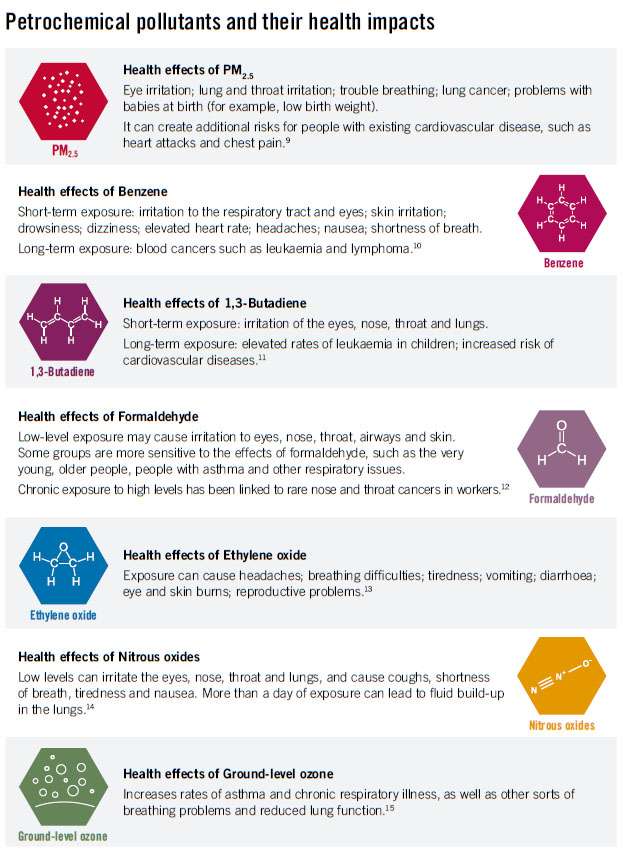

Amnesty International researchers detail the negative effects of over 600 petrochemical manufacturing sites concentrated around the Houston Ship Channel, a dredged waterway cut through the former Buffalo Bayou to connect East Houston industries to the Gulf of Mexico. It is one of the busiest waterways in the world, and the surrounding metropolitan cities hold 44% of the USA’s petrochem production capacity. Port Houston exports 59% of all US plastic resins, 73% of polyethylene (which is made into PET bottles). Pollutants present in alarming rates throughout the area include volatile organic compounds (VOCs), such as benzene, 1,3-butadiene, dioxane, ethylene, toluene, styrene and xylene; greenhouse gasses such as methane, carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide; and particulate matter (PM). Ozone, a secondary pollutant formed from the reaction between VOCs, oxides of nitrogen and sunlight, creates persistent toxic smog. Formaldehyde, another secondary pollutant created by reactions from mixed chemicals, is also present at dangerous levels.

From the Amnesty International report

Negative effects on the health of workers and residents range from headaches, dizziness, and vomiting as well as acute eye and lung irritation immediately after these chemicals are released, to asthma and other chronic respiratory illnesses, miscarriages and premature births, and numerous forms of cancer from repeated exposure. Benzene is particularly noxious – the WHO has said that exposure to benzene is “a major health concern” with no safe level of exposure. When accidents lead to large fires, high levels of benzene may be present in the air for over two weeks. Residents are rarely informed of chemical releases and they often struggle to access real-time information, with only unpleasant smells in the environment to tip them off to the danger.

Chemical disasters happen so frequently that they have become normalized for some residents. The AI report states that since 2021 there have been at least 15 chemical explosions, fires and toxic releases reported along the Houston Ship Channel, resulting in at least 28 workers being injured and one death. In 2023 alone, residents along the Houston Ship Channel experienced at least seven petrochemical disasters, including six fires. These figures only capture high-profile chemical disasters that receive media coverage and not the many less visible chemical emergencies that can still have devastating impacts.

The CAPECO disaster, 2009 in Puerto Rico, another region overburdened by environmental racism. Photo credit: US Chemical Safety Board

Hurricanes and heavy rains can also lead to catastrophic chemical spills. Even in ordinary conditions, the industry is careless about containing leaks and discharges. Between 2019 and 2021, nationwide 83% of refineries report violating their permitted limits on water pollutants. Communities closest to facility fencelines face the greatest harm and have the least time to react in the event of a catastrophic release. Those lower-income and racialized people can have up to 20 years shorter life expectancy compared to averages in the disproportionately affluent and white neighborhoods in western Houston, and much higher rates of all types of cancer.

The Houston metro area, rapidly expanding due to the burgeoning petroleum industry, is incredibly diverse but also extremely racially segregated. A lack of zoning regulations means that industrial facilities are sited right next to residential areas, almost always communities of color. The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) has clearly shown that they prioritize industry profits over these communities. State records show that TCEQ imposed penalties in less than 3% of cases of unpermitted pollution releases in recent years. A recent review called TCEQ commissioners “reluctant regulators” that encourage industry to “self-police.” Companies routinely avoid penalties for pollution releases by invoking the “affirmative defense,” a loophole in Texas laws that waives enforcement for air pollution that the company reports as “unplanned and unavoidable.”

AI reports that a former air pollution investigator for the City of Houston said, “These fines, they’re hardly a drop in the bucket… They mean nothing when the companies are pulling in billions of dollars a year.” A professor at Rice University explained, “The fines that companies pay are so small compared to the value of the petrochemical products they sell that they can be seen as a routine cost of doing business.” Frustration over underenforcement of already weak regulations was echoed by community members: “TCEQ is so ineffectual. Their fines are so limited. If you do the math for the violations… a company gets fined less than one person who’s affected by it would spend on medical bills. So, it’s very unfair.”

Making their disregard for residents’ health insultingly clear, in June 2023 the Texas legislature passed SB 471, stipulating that TCEQ does not need to investigate or even respond to certain complaints, especially from residents who have filed multiple complaints in the past.

Smoke and flares from petrochemical plants restarting after Hurricane Ida, 2021. Photo credit: Julie Dermansky

Louisiana – Cancer Alley

As if these stories about Houston were not appalling enough, the Human Rights Watch report about “Cancer Alley” exposes even more egregious environmental racism.

Between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, the banks of the Mississippi River are clustered with over 150 industrial facilities, nearly all of which process fossil fuels. This industry has become a defining feature of Louisiana’s identity. The state’s first oil well was drilled in 1901, and offshore oil extraction was innovated there in 1947. Production boomed and imports arrived as well. Today, Louisiana oil refineries account for one-sixth of the nation’s total capacity, with refined petroleum shipped abroad or pumped through pipelines to the various petrochem plants in Cancer Alley. The story is similar for methane gas. The most active methane gas market center in North America, the Henry Hub in Erath, interconnects nine interstate and three intrastate pipelines.

Louisiana has the highest per-capita energy consumption in the USA, mostly because of these industries (only 7% of total energy goes to homes). It has the worst pollution – according to an analysis of 2021 EPA data, the average Louisiana resident was exposed to four times more industrial pollutants than the average American. The majority of air pollution is occurring in Cancer Alley, as well as the majority of non-nitrate water pollution (nitrates come from fertilizers and are by far the highest source of water pollution). Huge amounts of toxic petrochem byproducts are leached or even dumped directly into the Mississippi River. The EPA found in 2016 and again in 2020 that residents of Cancer Alley were exposed to more than 10 times the health risks experienced by residents living elsewhere in the state. The most polluting operations are disproportionately concentrated within Black communities, and even more facilities are currently being built in those areas. Most residents in Cancer Alley are descendants of formerly enslaved people who had bought small parcels of old plantations. The industry moved in later, and many folks feel like the state prefers to let them move out or die off rather than protect their health and humanity.

Petrochemical plants right next to communities in “Cancer Alley.” Photo credit: Julie Dermansky

The HRW research indicates that many of the plants in Cancer Alley are constantly in “significant violation” of the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act. One site that they studied had faced six enforcement actions in the last three years, but was fined a mere $300 total. Since 2018, the EPA has required oil refineries to install air monitors that measure benzene at the fencelines of their facilities. Data from these monitors indicate that actual emissions can be as much as 28 times the amounts reported by companies. So far only 13 petrochem facilities nationwide have been compelled to install these monitors, and only a few have collected enough data to be useful. Those in Cancer Alley are routinely emitting benzene well above legal limits.

But state regulators do nothing to change this situation. Interviewees told HRW that the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ) was actively “hostile” to their interests, acting as a “rubber stamp” and a “revolving door” for the industry. A 2021 audit found that LDEQ failed to adequately track facilities’ emissions reports, including facilities that failed to submit reports entirely. Penalties were not tracked, and frequently were not paid. It takes an average of 20 months for LDEQ to issue enforcement actions after known violations.

Meanwhile, residents continue to be exposed daily to the same chemicals described above, and feel the same effects. The planned expansions of petrochem plants and pipelines promise to worsen these conditions. Pipelines (including carbon pipelines, which are being built to facilitate the false solution of “carbon sequestration“) are much less visible yet insidious, since they receive little attention from regulators, but have high incidences of leaks and spills caused by hurricanes as well as normal wear and tear, and their construction cuts apart and destroys sensitive bayou ecosystems, thereby amplifying all the other negative effects of the industry.

The petrochemical industry has no right to treat our community as a sacrifice zone. It is high time for regulators, legislators, NGOs, and the public to fight for the urgent needs of environmental justice communities.

– Juan Parras, TEJAS

Jeff Landry, a fossil fuel industry lawyer and now the state’s governor, has been an outspoken defender of the status quo. It was his lawsuits that negated Obama’s Clean Power Plan and Biden’s fossil fuel leasing ban. In early 2023, the EPA had been negotiating improvements to LDEQ’s permitting process, such as assessments of cumulative impacts from existing health hazards and racial discrimination. But Landry sued the federal government again, making a sort of “reverse racism” argument that unless a law explicitly says that its intended purpose is to harm people of color, any claims that discrimination is occurring are politically-motivated attacks by partisan regulators “moonlight[ing] as social justice warriors.” One month after the dispute was filed, the EPA abandoned its Title VI investigation, presumably in fear of a judge agreeing with Landry and setting a precedent which would limit their ability to use the Civil Rights Act in the future. Recently, Landry made a highly unusual move by initiating a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) suit against the EPA, collecting the names and contact information of activists and journalists who have been trying for years to hold LDEQ accountable. This is widely viewed as an aggressive intimidation tactic aimed at silencing environmental justice communities.

Members of Inclusive Louisiana, RISE St. James, and Mount Triumph Baptist Church announcing a 2023 lawsuit requesting a moratorium on new oil and gas industry in St. James Parish. Photo credit: Antonia Juhasz, Human Rights Watch

Why These Reports Matter

Framing the daily activities of the petrochem industry as human rights abuses is an important step in holding polluters accountable, as it brings various UN resolutions into the conversation, as detailed in both reports. The communities of the Houston Ship Channel and Cancer Alley, and other overburdened communities in the USA, can be seen as the “Global South within the North” because the non-white, non-affluent residents often bear little responsibility for these harms yet struggle to live amidst the impacts.

Juan Parras of Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Service (TEJAS), a close ally of JTA, responded to these reports by speaking about the experience in his neighborhood: “Manchester is the most polluted and most densely industrialized community in Houston. We are overwhelmed with the excessive burdens of environmental racism – health problems, poisoned air and water, and constant stress. We have tried numerous times to bring this to the attention of regulators, but they seem to view the situation as unfortunate yet irreversible. Although we often feel hopeless, this invocation of international human rights treaties may finally put enough pressure on government to hold companies accountable. The petrochemical industry has no right to treat our community as a sacrifice zone. It is high time for regulators, legislators, NGOs, and the public to fight for the urgent needs of environmental justice communities.”

In fact, these human rights abuses extend far beyond frontline workers and fenceline communities. Without major reductions in the manufacturing of plastics and other petrochemicals, even 100% renewable energy cannot keep us within global emissions targets. But this industry continues to grow exponentially. The big oil and gas companies are counting on it to keep their profit margins high even as vehicle and power plant technologies change. Climate chaos will have at least some effect on every part of the planet, but the Gulf Coast is one of the very most vulnerable areas, with rising sea levels, increasingly strong storms, and sweltering heat. It is ironic that the industries located in that region are some of those chiefly responsible for the impending catastrophe. Yet the executives and stockholders of the corporations that own these facilities live far away. They no doubt intend to wring out as much money as possible right now, then shutter the plants when forced to make safety improvements for health or disaster readiness reasons. The communities that have been condemned as sacrifice zones will be left behind.

Houston playground adjacent to refinery. Photo credit: Lauren Murphy, Amnesty International

In addition to the worldwide human rights abuses which are perpetrated by those responsible for global warming, the presence of petrochem byproducts – and even those products themselves – constitute an unjust toxic trespass. A recent report by Defend Our Health studies the numerous negative impacts of polyethylene terephthalate (PET, the substance used to make clear plastic drink bottles) from extraction, manufacturing, and waste. The entire PET supply chain spans not only the Gulf Coast region but also many other locations around the USA. The majority of those facilities are located in low-income communities of color.

The plastics industry has consistently lied to the public about the safety and recyclability of their products. Another recent report by Center for Climate Integrity shows that well over 90% of plastics have been landfilled, incinerated, or leaked into waterways, ecosystems and communities. Despite industry claims that recycling can solve the problem, evidence collected from the industry itself shows that this unacceptable trashing of our health and environments will never change. Very few plastic products are actually recyclable, and manufacturers have a powerful profit incentive to ensure that everything they sell is single-use, driving endless demand for more production. All their talk about new recycling technologies is deceptive nonsense – so-called “advanced recycling” means melting plastic back into oil and burning it as fuel, and the majority of the facilities designed to do this have not been profitable and have closed a few years after swindling public money out of lucrative municipal contracts. Despite decades of PR campaigns fooling people into thinking that they just need to “do their part” by placing plastic containers into curbside recycling bins, plastics pollution has become one of our most serious crises, with microplastics found even in clouds.

Small-scale plastic recycling in Indonesia, one of the countries to which Global North waste management companies send plastic trash when it cannot be recycled at a profit. The man in the foreground is cooling melted plastic into bricks which can be sold to manufacturers, inhaling toxic fumes in the process. Photo credit: Focusfeel [wikimedia commons]

EJ Communities Need a Just Transition

We must stop making all this plastic junk designed expressly to become garbage as quickly as possible. While there may be some limited defensible uses of plastics in the fields of medicine and electronics, nearly all of the products being made today are completely unnecessary. Plastics cause so much more harm than good.

We need to uplift the voices of those fighting for their lives in the face of environmental racism and toxic trespass, supporting them to come together, frontline workers and fenceline communities united in creative problem-solving, finding real solutions that can build regenerative solidarity economies that move them toward a healthy and dignified future. These frontliners are already advocating numerous policy solutions. First, tax breaks and subsidies that currently prop up fossil fuel extraction and petrochemical production must be reallocated to research and new facilities for benign, sustainable chemistry. And then, an option that would be easy to achieve immediately would be to expand and replicate existing “orphaned well programs” in which governments and companies collaborate to pay local workers to safely clean up abandoned wellsites and restore ecosystems (the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law included $4.7 billion to do just this, a tiny baby step toward plugging the estimated 300,000-800,000 unidentified orphaned wells across the USA). State legislators should provide funds for additional just transition initiatives similar to California’s HEAL initiative. Federal funding from the Inflation Reduction Act should grow community resilience by building locally-controlled small-scale renewable energy and public transportation. A union-led initiative called the Texas Climate Jobs Project is organizing efforts to do exactly that as the basis for a truly transformative just transition. Their study shows that this transition can create 1.1 million jobs in Texas alone (and cites other researchers’ estimate of 25 million jobs nationwide).

The great potential of a just transition is true not only in Texas, but everywhere, and it goes far beyond job creation. An illuminating report by the Tellus Institute, now over a decade old but more relevant than ever, demonstrates how transitioning our waste management systems to keep materials out of landfills and incinerators by reusing and repurposing as much as possible could create 2.3 million jobs nationwide, as well as reduce emissions and, crucially, slash production of toxic plastics, leading to health improvements in countless communities. California’s Recology is at the leading edge of this increasingly popular transition toward “zero waste.”

Workers sort recyclables at Recology facility, Davis CA. Photo credit: Recology

At every level of public discourse and governance we must debunk the industry lies about “plastics circularity” and demonstrate real circular economies, based on principles of zero waste, localized production, traditional ecological knowledge, and grassroots democracy. One way that JTA is trying to do so is by engaging with the ongoing negotiations to create a UN Treaty on Plastics Pollution, fighting to maintain the integrity of the “just transition” vision in the face of mounting corporate cooptation. Another is working with the Environmental Justice Communities Against Plastics (EJCAP) coalition to push California lawmakers and regulators to close loopholes and improve effectiveness in recent plastic waste reduction law SB 54.

Other groups are beginning to find success with tactics that apply pressure upstream from the manufacturers, pushing pension funds, universities and banks to divest from polluters, demanding that insurance companies revoke policies for facilities that endanger the planet, and organizing the labor sector within predatory private equity firms that own many of the worst offenders.

An additional path that surely will be pursued by states, municipalities and advocacy groups is litigation demanding payments from the offending corporations, both in terms of damages to victims and compensation for the mounting costs of disposal. The fossil fuel companies should be legally restricted and financially reprimanded the same way that big tobacco companies were handled. In tandem with this top-down approach, concerned citizens can advocate for the bottom-up demand to change our laws to roll back the suite of unfair court rulings collectively known as “corporate rights” and to ensure rights for communities and environments (the movement to establish “legal rights for rivers” is succeeding around the world).

The Mississippi River. Photo credit: Ken Lund [wikimedia commons]

Fossil fuel companies have seen record profits in the years since the pandemic began. These profits belie the excuse that inflation is caused by supply chain disruptions. It has become increasingly clear that this lying, cheating, psychopathic industry is at the climax of its abusive behavior of hoovering up heaps of cash by extracting the wealth of the earth while externalizing all the costs onto EJ communities and ecosystems.

We must not let oil and gas corporations continue their human rights abuses by allowing them to sidestep into equally harmful plastics and petrochemicals. We must work together to change our economic systems into something life-giving and holistic, respecting our neighbors and environments, repairing our past harms, and regenerating our relations. We must build the best alternatives by cultivating community power and grassroots democracy. Please take the terrible findings of these reports and transform them, not into passive hopes and prayers for the unfortunate folks on the frontlines and fencelines, but a strong motivation and vigilant commitment to struggle with the workers and communities organizing for a just transition. Remember, “Transitions are inevitable. Justice is not.”